Expected Shortfall (ES)

Expected Shortfall (ES): Understanding Risk Beyond Value at Risk

Expected Shortfall (ES), also known as Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), is a risk management measure used in finance to evaluate potential losses during extreme market events or periods of financial stress. It provides a deeper analysis of risk compared to Value at Risk (VaR) by considering not just the maximum potential loss within a given confidence interval but also the average losses that may occur in the tail end of the distribution of potential outcomes.

Expected Shortfall is widely used by financial institutions, investment managers, and risk analysts to assess downside risks in portfolios, investments, and financial strategies. It is a key component of stress testing, capital adequacy assessments, and portfolio risk management.

Understanding the Basics of Expected Shortfall

At its core, Expected Shortfall measures the average of all potential losses that exceed a given Value at Risk threshold. While Value at Risk quantifies the worst-case loss within a specified probability level, ES considers the average losses in the tail (the most extreme 5%, 1%, or other quantiles of the distribution).

For instance, if an investor sets a 95% confidence interval, VaR tells us the maximum amount an investor would expect to lose with only a 5% probability of worse outcomes. Expected Shortfall goes one step further by quantifying the average of these worst-case outcomes in that tail region.

This makes Expected Shortfall particularly useful when assessing extreme risk events, such as market crashes, economic downturns, or financial crises.

How Expected Shortfall is Calculated

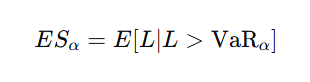

Expected Shortfall is mathematically defined as the conditional expected value of losses in the tail region (beyond the VaR threshold). Specifically:

Expected Shortfall = Average of all losses that are worse than the Value at Risk (VaR) at a given confidence level.

General Formula

Let’s assume that VaRα_\alpha represents the Value at Risk at confidence level α\alpha. The Expected Shortfall can be expressed as:

Where:

L = Loss under consideration

α = Confidence level (e.g., 95%, 99%)

This means that Expected Shortfall is the expected value of all losses beyond the VaR threshold for a given confidence interval. Unlike VaR, which provides a single number, Expected Shortfall considers all outcomes in the tail, offering a fuller picture of risk.

Comparison of Expected Shortfall to Value at Risk (VaR)

Although VaR is a widely-used risk measure, it has limitations that Expected Shortfall addresses:

VaR Limitation: VaR provides the maximum potential loss at a certain confidence level but does not give insight into how severe losses might be if they exceed this threshold. It essentially cuts off the analysis at a specific quantile.

Expected Shortfall Advantage: ES examines the average losses in the tail beyond the VaR threshold, offering a broader view of extreme financial risks.

For example:

VaR might show that the maximum expected loss at a 95% confidence level is $1 million.

Expected Shortfall would then quantify the average loss in the 5% worst-case scenarios, perhaps revealing that the average expected loss is $1.5 million.

Expected Shortfall is, therefore, considered a more conservative and comprehensive risk measure compared to VaR.

Applications of Expected Shortfall

Expected Shortfall is applied across numerous financial and risk management settings, including:

Risk Management

Financial institutions use ES to estimate the amount of capital reserves required to absorb extreme losses under adverse market conditions. It provides insights into tail-risk scenarios that could deplete capital buffers.Portfolio Management

Investment managers rely on ES to optimize portfolios, ensuring that they are resilient to extreme market movements. ES allows for better diversification by assessing downside risks across different assets.Stress Testing

Financial institutions use Expected Shortfall to simulate market crises and extreme economic scenarios. It helps gauge how a portfolio or financial institution would perform under extreme market stress.Regulatory Compliance

Regulators, such as central banks and international financial oversight bodies, use Expected Shortfall in stress tests and capital adequacy requirements to ensure that banks and financial institutions maintain sufficient capital to weather severe losses.Derivatives Pricing and Risk Hedging

Traders use ES to price complex derivatives and design hedging strategies that protect against rare but catastrophic market moves.

Advantages of Expected Shortfall

Tail Risk Sensitivity

Expected Shortfall explicitly measures tail risk, focusing on extreme losses that might not be captured by VaR alone.Comprehensive Risk Analysis

ES provides insights into the average severity of extreme losses rather than just a single threshold (VaR), allowing for a better understanding of worst-case scenarios.More Robust Stress Testing

By focusing on losses in the tail, Expected Shortfall allows financial institutions to conduct more realistic stress testing to identify vulnerabilities during extreme events.Conservatism

Since ES incorporates average losses in the worst-case scenarios, it is a more conservative risk measure than VaR, which helps ensure financial stability.

Limitations of Expected Shortfall

While Expected Shortfall is a valuable risk management tool, it does come with challenges:

Model Dependence

Like VaR, the calculation of ES relies on statistical models and assumptions about market behavior. If these models are incorrect or fail to account for market anomalies, Expected Shortfall may be inaccurate.Data-Intensive

Calculating ES typically requires extensive historical data to identify tail losses. In markets with limited historical data or rare catastrophic events, this can lead to estimation errors.Computational Complexity

Unlike VaR, which can often be calculated quickly, computing Expected Shortfall can be computationally intensive, especially for large portfolios or complex derivatives.Historical Data Risk

Past extreme market events may not always be reliable indicators of future events, leading to potential biases in Expected Shortfall estimates.

Example: Calculating Expected Shortfall

Let’s consider a simplified example:

Suppose a portfolio has historical daily losses over a 1-year period. Using statistical methods or historical analysis, the VaR at a 95% confidence level is calculated to be $10 million. To find the Expected Shortfall at the same confidence level, we examine the average of all losses that are worse than the $10 million threshold.

If the worst 5% of the distribution (losses greater than $10 million) has losses ranging between $10 million and $15 million, the average (Expected Shortfall) could be $12 million. This tells risk managers that, in the worst 5% of market outcomes, the expected average loss would be $12 million—higher than just the VaR number alone.

Conclusion

Expected Shortfall (ES) is an advanced risk measure that builds on Value at Risk by focusing on average losses in the tail end of a probability distribution, beyond the VaR threshold. It provides a more conservative and holistic perspective of risk by quantifying the severity of extreme market events.

Financial institutions, portfolio managers, and regulators increasingly rely on Expected Shortfall for stress testing, capital adequacy, and portfolio optimization because of its focus on worst-case scenarios. Although computationally more intensive and reliant on historical data, ES offers significant value in a world of unpredictable market movements and economic shocks.